An appetite for growth Brazil's cattle ranchers are embracing change

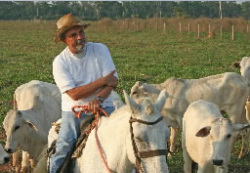

James King Carr De Muzio working cattle.

By Barry Shlachter

December 2006

VERA, Brazil - James King Carr De Muzio started cattle ranching later in life. But the easy-mannered 53-year-old Brazilian doctor and rancher feels as comfortable in the saddle as he does wearing surgical scrubs.

De Muzio - who says his mixed ancestry, unusual even in Brazil, includes Alabamans who joined a colony of Confederates after the Civil War on one side and a "tossed salad" Spanish-Italian-African heritage on the !other - counts himself among producers enlarging their cattle holdings as the country's beef industry continues a seemingly insatiable growth.

Starting with two cows he received for delivering a baby during Brazil's 1994 currency crisis, De Muzio built his herd to more than 1,000, then scaled back to 500 after a dry summer. He says he's reshaping his operation, gearing it toward yearling stocker steers. He remains bullish on his country's cattle industry, which has been hobbled by a lack of paved roads, by quality issues, and by periodic outbreaks of disease that keep all but cooked beef out of the United States.

"It's still something new for me," he said of ranching. "I like medicine, but this is more than a hobby. I can afford to lose some money .... but I can't throw money away."

Brazil's herd, conservatively estimated at 170 million head (the nation's beef export association figures 204 million), is the world's largest - there are about 97 million U.S. beef cattle - and there is every indication that Brazilians like De Muzio will make it an even bigger ranching country.

In 2004, Brazil became the world's largest beef exporter by volume, according to the U.S. Agriculture Department. Disease, sanitary issues at slaughter plants, and the sale of lower-priced cuts account for why it still trails Australia in export value.

Incidences of highly contagious foot-and-mouth disease in some parts of Brazilprevent exports of fresh, chilled and frozen beef to some key markets, including the U.S. and Japan.

But with exports to 150 other countries, "losing a few hasn't had a discernible impact on the numbers," says Steve Kay of Cattle Buyers Weekly, based in Petaluma, Calif.

Russia and 55 other countries stopped imports from Brazilian states affected by foot-and-mouth disease last December but removed the ban on major producing states like Mato Grosso deemed clear of the infection in August. Nonetheless, Brazil's exports from January through September 2006 rose 17.6 percent in cash value and 3.8 percent in volume compared with a year earlier, according to the Brazilian Beef Industry and Exporters Association.

Aside from being hormone-free, more than 90 percent of Brazilian cattle are grass-fed and therefore unlikely to contract mad cow disease from tainted feed. This pleases safety-conscious European consumers. Only cooked Brazilian beef can be imported into the United States, the biggest customer for this processed meat.

The relatively low price of Brazilian beef attracts orders from Russia, its No. 1 customer, and Middle Eastern countries. Overall, Brazil accounts for a quarter of global beef exports.

Right now, few American ranchers appear concerned about Brazilian competition. Moreover, more expensive grain-fed beef from the United States has ended up in foreign markets, except for some by-products like tongue, U.S. producers say.

The sanguine American reaction to Brazil's runaway export growth might well be justified - if Brazilians don't expand their relatively tiny base of feedlots and compete head to head with higher-quality beef. Less than 10 percent of cattle here go through feedlots, where a diet of grain adds pounds quickly.

But low corn and soybean prices, compounded by an abundance of supply often in the same regions, are making feedlots much more attractive to Brazilian cattlemen.

Carlos Kind operates the country's 11th-biggest feedlot, Boitel (an acronym for "Bovine Hotel") near Rio Verde in Goias state. The feedlot can handle 12,500 cattle; about 75 percent are owned by him and his partner. He says Brazilian ranchers are increasingly using feedlots to produce higher-grade beef cattle.

"We may now represent less than a tenth of cattle production, but feedlots are growing at 20 percent a year," Kind said through an interpreter. "The big feedlots are getting bigger and there are more small ones. As for me, I am going to invest in better feed - cornmeal and soy - to get the steers finished faster. We've got the land and the grain. The problem is that banks generally don't lend to feedlots."

A sense of potential

Texas rancher Gary McGehee has seen the Brazilian potential, and he is worried.

Although the American industry has derided grass-fed beef as inferior to the U.S. corn-fed variety, McGehee said he was uncomfortably impressed by the grass-fed meat he ate during a visit to Brazil.

"The steaks were great, prepared well. That kind of stuff scares me," he said during a call from the West Texas town of Mertzon.

Brazil should no longer be dismissed as just another Third World country, McGehee cautioned.

"They are competitive with us," he said. "Although we might export less than 7 percent of our beef, if the price of cattle drops 3 or 4 percent because of Brazilian competition, that is going to have an effect on me. Eventually, they are coming to our own market and we're going to have to deal with it."

At the Boitel feedlot in central west Brazil, a 64-year-old cattleman named Helvecio Pereira sized up Kind's operation. He was in Rio Verde to find at least one more feedlot for his livestock.

"Cattle ranching has changed totally in the past 30 years, and it's changing faster all the time," Pereira said. "We know the techniques from the United States - how you feed the cattle, put weight on. But it wasn't that feasible until now. The prices weren't there."

A trained agronomist, Pereira said he started in 1968. His family bought land at $20 an acre near Mozartlandia, in Goias state, then borrowed money to clear it.

"There were no roads, no house, electricity, just jungle," he said, telling a familiar story among Brazil's pioneer ranchers. "It took 20 years. Now we have 19,000 acres." He declined to say how large his herd is, but a person in the industry estimated that Pereira holds at least 3,500 head.

Pereira said everything changed when profits dropped after the 1994 currency crisis, when the government's fiscal policy destroyed the value of the currency, the cruzeiro, almost overnight, decimating people's life savings. The crunch forced greater efficiency and specialization among cattlemen.

"We couldn't make money on just speculation and currency fluctuations as in the past," Pereira said. "Before 1994, it took us 48 to 58 months, from start to finish, to produce a slaughter-weight steer. Now we can do it in 24 to 30 months - with even better quality."

Feedlots became more prominent in Brazil after 1994, said Pereira. He has used a feedlot between his ranch and the main beef cattle market in Sao Paulo, Brazil's financial capital and largest city.

"That's where you get top dollar," he said.

Pereira said relatively few Brazilian producers hedge their risk as he does by striking future deals for cattle.

Land is no longer $20 an acre, but Texas-reared rancher John Cain Carter said some can still be found for $150. About half must be set aside as an environmental reserve. Then there's the cost of clearing heavy brush.

"It's still cheaper than $2,000-an-acre range near Castroville, Texas," said Carter, a San Antonio native who attended Texas Christian University's ranch management program, where he met his Brazilian wife, Kika. They operate a 20,000-acre ranch near the Xingu River Basin, a tributary of the Amazon.

Brazil's advantages

Besides cheap land, Brazil's advantages for the cattle industry include fairly reliable rainfall, experienced and inexpensive labor, and hardy, drought-resistant forage !grass.

As for labor, "I pay about 33 percent more than others, but I demand more," Carter said. He pays 800 reais - about $375 a month - and his workers get free beef and use of the ranch's motorcycle and jeep.

"In Brazil, you can pay off your ranch running cattle in five to seven years," he said. "You can't do that in the United States."

But it's not all clover.

Things taken for granted in Texas, like farm-to-market roads and access to the electrical grid, often don't exist in Brazil. Carter said he spent $100,000 putting in a hydroelectric generator.

Ranchers have little incentive to produce top-quality animals, because there's no widely established grading system. Unlike in the United States, where ranchers are rewarded for producing leaner, more tender beef, "cattle here are sold purely by weight," Carter said.

De Muzio agreed.

"When I sell steers, it's sight unseen," he said. Auctions are mainly for breeding stock.

But things might change, said Carter, who has been consulting with Grupo Brascan, a Canadian-owned operation that bought the Brazilian assets of Texas' historic King Ranch. Brascan is now talking with traders to see what percentage of fat they want in the carcasses.

"They have 50,000 brood cows, and there's the potential to sustain whole restaurant chains," Carter said.

In Vera, De Muzio put his first two cows on about 370 acres of uncleared land, then added to the holding over the years. He now has 2,440 acres that cost about $200 per acre on average.

De Muzio later invested in a cattle operation with a friend. When a wealthy soybean farmer wanted to buy the land, De Muzio moved 130 cows and three bulls to his ranch, where by then he had 60 head. With the help of one full-time employee, he built the herd to more than 1,000 head. Then last year's dry season hit.

"It was four months of dryness - dry, dry, dry," he said, repeating the word in a drawl, a legacy of his mother's Alabama heritage.

He culled his herd and decided to concentrate on buying weaned calves and selling them after two years of grazing. Brazilian producers are only now beginning to specialize in cow-calf operations or weaned yearlings. But De Muzio decided that running a cow-calf operation "just doesn't pay."

"I figured it out myself, especially when I saw them starving last year," he said. "I lost two to starvation. Cows eat too much."

During the drought, he spent about $7,000 on silage.

"Then," he says, "it rained. I promised myself I wouldn't go through that again."

Brazilian cattleman Helvecio Pereira is one of the early producers to specialize and finish his cattle in feedlots. “Cattle ranching has changed totally in the past 30 years and it’s changing faster all the time,” Pereira said. “We know the techniques from the United States — how you feed the cattle, put weight on. But it wasn’t feasible until now. The prices weren’t there.” Photo by Barry Shlachter