|

Fossey: An Expert Nearly As Elusive As Her Subjects

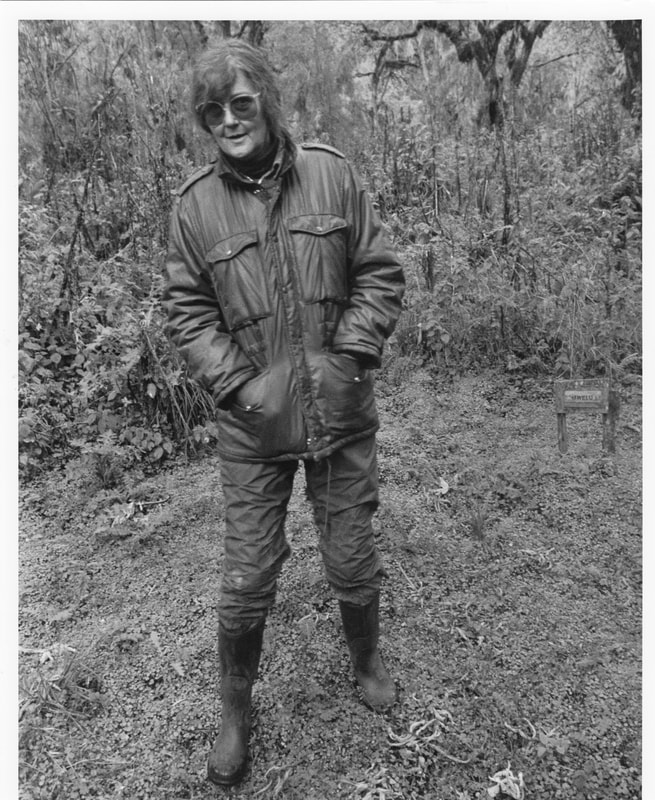

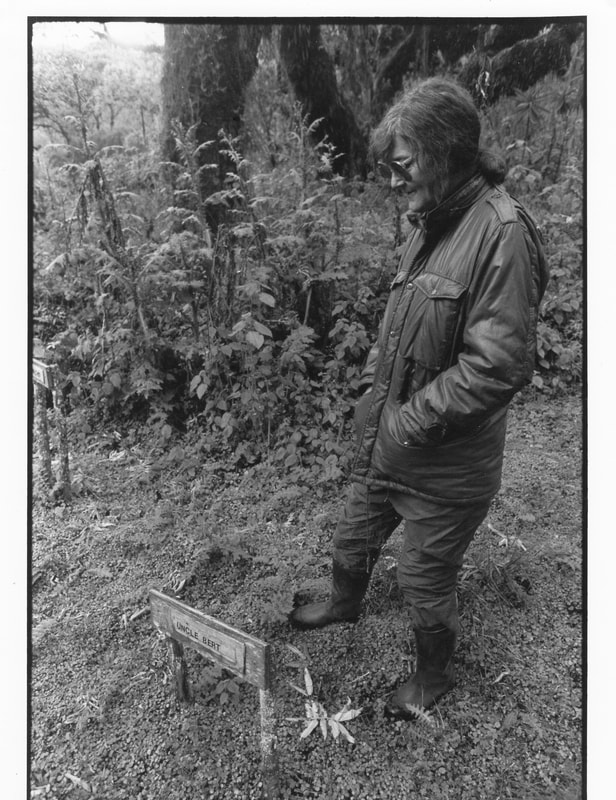

January 12, 1986|By Barry Shlachter, Special to The Philadelphia Inquirer VIRUNGA MOUNTAINS, Rwanda — Much of what man knows today about the mountain gorilla comes from research done during the last 26 years by two scientists, George B. Schaller and Dian Fossey. Schaller went on to complete celebrated studies of the lion in the Serengeti and the snow leopard in the Himalayas. But until her stabbing death here less than three weeks ago, Dian Fossey had remained true to the gorilla. It was Fossey who is largely credited with pioneering the habituation techniques that made it possible for tourists to come to the gorillas of Rwanda. We could not possibly have known that we would be among the last few outsiders to visit Fossey before her death. Ironically, our encounter with this remarkable woman also made it clear that she had become something of a controversial figure in the year before she died. The animosities she created among some of the local people in her adopted jungle habitat only deepen the mystery that surrounds her slaying. What follows is an account of our meeting with Fossey in May 1985. CHALLENGING JOURNEY When we decided to pay a visit to Dian Fossey at her Karisoke Research Station in the Virungas, little did we know it would prove to be the most challenging part of our Rwandan journey. In spite - or perhaps, because - of the notoriety generated by her studies, a television documentary, an autobiograpy (Gorillas in the Mist) and articles in the National Geographic Society's magazine and elsewhere, Fossey had never suffered courtesy callers gladly, we had heard. Two weeks before our arrival, two women researchers from Stanford University made the arduous 10,000-foot climb to her cabin only to be told to get lost. A West German tourist got an even less hospitable welcome years before - a shot fired over his head. Everyone we ran into warned of a possibly hostile reception at Karisoke, situated on park property. While nothing critical had yet appeared in the press about Fossey, word circulated in the African wildlife community that her eccentric behavior could be hurting the conservation effort. There was a feeling that 18 years on the mountain - interrupted only by a three-year teaching assignment at Cornell University - was too long and that she was losing touch with reality. Some reports said she was dying. There was also speculation that local animosity against the American researcher might even have motivated the killing of habituated gorillas, as a way to get back at her. FUNDS GOING ELSEWHERE ''The major conservation organizations have decided to put their money in the Mountain Gorilla Project instead of continuing to fund Dian Fossey's work," said Esmond Bradley Martin, a Long Island-born geographer and Kenya resident who has worked on numerous efforts to protect wildlife in Africa. "Some conservationists disagree with her overall philosophy on the best way to save gorillas," he said. "They believe Fossey overemphasizes anti- poaching as the only method to preserve this endangered species." After some searching, we found a guide willing to take us up the mountain. Many local Rwandans said they feared going near Fossey, who was in her early 50s. They called her Nyiramachabelli, which in the Kinryanda language means, ''The Old Lady Who Lives in the Forest Without a Man." Fossey, we were told, had painted a four-letter English expletive on the side of a cow that had wandered into the park. (Only Kinryanda and French are spoken here.) Before going to Cornell, she was reprimanded by a magistrate in nearby Ruhengeri for taking hostage the small daughter of a Rwandan farmer. Accusing the man of abducting a baby gorilla, she had offered the suspected poacher a one-for-one trade, said park officials who described themselves as friends of the American woman. While we knew we would possibly be unwelcome, we wanted to see whether Fossey's activities were counterproductive, since she was still collecting public contributions in the United States through a nonprofit foundation, the Ithaca, N.Y.-based Digit Fund. It was named for Digit, a gorilla she had personally habituated whose 1977 slaying - reported by Walter Cronkite on the CBS Evening News - triggered immense concern for the threatened species. RUGGED PATHWAY The hike was more difficult than the ones in pursuit of the gorillas. The sharp angle of the climb was aggravated by thick mud that kept sucking off Martin's running shoes. Though the rest of us wore rubber boots, we also slipped and landed in bunches of stinging nettles. After 90 minutes we reached a clearing of unearthly charm. The unfamiliar, barkless trees emerging from the mist gave it the feel of a ghostly film set. Then a collection of quite ordinary-looking frame structures with corrugated metal roofs came into view. The Karisoke Research Station. A man who introduced himself as Bazira, Fossey's Rwandan servant, insisted she was not at home. He kept denying her presence even when we later overheard him speaking to her inside a cabin. "A woman's voice? That was the parrot," he explained nervously. We sent Bazira back in with a note. Ten minutes later the tall, rugged-looking American scientist walked down the path to a picnic table where we had settled ourselves. Martin relayed greetings from a mutual friend and she hesitantly sat down with us for a chat that was to last until light began falling. Her raspy voice and difficult breathing were due to emphysema, which she said was in an advanced stage. At one point she abruptly got up and approached our guide. Stooping to pick up two blades of grass, she carefully entwined them and then placed the small green braid in the path between them, mumbling something in Kinryanda. A WARNING Conspicuously laying such an object in front of an enemy was a traditional way of warning him not to proceed farther, the Rwandan guide later explained. At another point before we left, we found the guide hiding in the research center's tool shed, disoriented and literally shivering from fright. "She is very evil," he said, recounting the incident in French. "She told me, 'Why did you bring these tourists here? If you or your people come here again, there will be death....'" THE INTERVIEW Martin and I, and Nitin Madhvani, a young Ugandan industrialist who accompanied us, were unaware of what had transpired between the two of them at the time. Turning from the guide, who backed away, Fossey smiled warmly and invited us to her cabin for beer. "That's a red-headed parrot. No, it's a green-headed parrot," she said as we walked, then made cooing sounds. "Here Tiger, here Tiger," she called out without explaining to whom or what. We followed her into a small, well-tended plot adjacent to her house where 13 wooden markers inscribed with names were hammered into the earth. It was a burial ground for the gorillas habituated by her. All but one, she said, had been slain by local poachers. Digit was interred there, as was an ape she had named Uncle Bert. "I hate your kind," she announced when I told her I was a journalist. Expecting the interview to be cut short, she surprised us by turning friendlier and dropping her reserve as we talked. "The gorillas must have been curious (about) that," she said as she leaned over to touch Martin's bushy, prematurely white hair. She became animated, even charismatic, when I switched on my tape recorder. PRICE OF ILLNESS Her lung ailment, for which she received no regular care, limited contact with her apes since she could no longer walk far, she informed us, puffing continuously on her local Impala brand of cigarettes. Yes, she knew that smoking combined with the forest damp would probably shorten her life. There was talk in Kigali and elsewhere that she hoped to die among her beloved gorillas; that day Fossey said she would stay until she no longer could help protect them. Although too sick to carry out research, she could still supervise anti- poaching patrols financed by the Digit Fund, she asserted. Fossey complained about "sniping" against her by critics in the wildlife community. But she returned fire by charging that the Gorilla Mountain Project was inept. "They sleep in tents like Boy Scouts," she sneered. "My men sleep beneath trees, undetected by poachers." The week before our arrival, her team did capture a notorious poacher named Sebahuta. "He made a full confession and I didn't have to pull out his eyelashes or castrate him," she laughed, referring to rumors of harsh treatment she supposedly dispenses to apprehended poachers. Fossey, dressed in a maroon ski parka, rubber boots and waterproof leggings over blue jeans, told us she had given up a fiance years ago to devote her life to Rwanda's mountain gorillas. "I have no friends," she confided with no trace of regret. "The more you learn about the dignity of the gorilla, the more you want to avoid people." <script> (function(i,s,o,g,r,a,m){i['GoogleAnalyticsObject']=r;i[r]=i[r]||function(){ (i[r].q=i[r].q||[]).push(arguments)},i[r].l=1*new Date();a=s.createElement(o), m=s.getElementsByTagName(o)[0];a.async=1;a.src=g;m.parentNode.insertBefore(a,m) })(window,document,'script','//www.google-analytics.com/analytics.js','ga'); ga('create', 'UA-55034894-1', 'auto'); ga('send', 'pageview'); </script> |