Guanajuato

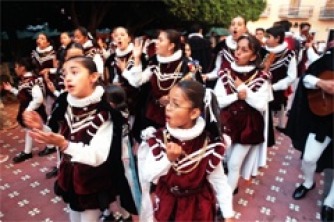

Tuna Colegiata Real de Guanajuato, one of a number of strolling

troubadour groups, is made up of children as young as 4. For a

bargain $6, you can follow the singers through the winding streets,

then receive a small ceramic flask of tequila cocktail to down

while listening to songs that range from medieval ballads to The

Impossible Dream (in Spanish).

By Barry Shlachter

GUANAJUATO, Mexico _ The idea was to have a Mexican adventure, a tight-budget

adventure, but one that my 15-year-old son might remember and hopefully even inspire him to

crack his Spanish books.

There were no set plans, no reservations. We’d drive to the border then hop a bus to the

Central Highlands for some relief from the broiling Texas sun in July and meander about, hitting

three or four of the famed ``silver’‘ cities of colonial Mexico.

After a one-night stopover in San Luis Potosi, my son and I made it to Guanajuato and

went no farther. For 11 days, we had one magical encounter after another. Zack simply didn’t

want to leave. And neither did I.

The city is among the most distinctive of the old cities and deemed worthy of

preservation by UNESCO as part of mankind’s patrimony for its narrow streets and historic

buildings. A labyrinth of stone-walled, underground roads kept much of the ground level

pedestrial friendly.

Something is always happening around the Jardin de la Union, the main plaza. We met

artists and writers and musicians off the tourist track at a joint called Barfly. We got hauled into a

wedding party and found ourselves present when a marriage proposal was made _ and laughed off.

It was Zack’s first trip to Mexico and I wanted him to see beyond the skewered

stereotypes, find an incentive to seriously study Spanish and, basically, have a great time,

knowing there might not be too many more trips he’d want to share with the old man.

There were howls from co-workers when I announced a mid-summer trip to Mexico.

Further guffaws when I said it would be by bus.

Though our state neighbors Mexico, my colleagues like many Americans were simply

unaware of the pleasant summer temperatures, mid-80s in the afternoon, mercury dropping to 55

or lower at night in the Mexican central highlands, the Bajio. Guanajuato is at an altitude of

6,700 feet.

And far from being broken down old school buses, the vehicles we took were comfortable

Mercedes Marco Polo conveyances with on-board restrooms and videos. We caught films by

Kevin Spacey and Robin Williams [in the original English with Spanish subtitles] to pass the 10-

hour rides.

With a bit more planning, we could have flown to Leon, about 90 minutes by road from

Guanajuato, or to Mexico City, some four hours. The one-way bus fare from Nueva Laredo on

the border to Guanajuato is less than $65.

Silver mining makes little money for Guanajuato these days, and this very traditional

town has accepted its economic dependence on turistas. To encourage visits, the city sponsors a

festival honoring Cervantes, the author of /{Don Quijote,/} and an international short film

festival.

Surprisingly, few residents have chosen to alter their lives to cater to foreigners. A local

journalist said the old middle class is in denial. The streets, even way after dark, are safe and the

people are generally friendly. Remarkably few waiters and hotel clerks speak English, although

many patiently work with one’s not-quite survival Spanish.

Should you want to improve your grasp of the language, Guanajuato is home to a plethora

of Spanish schools, ranging from the well-established Academia Falcon to numerous

competitors, some amazingly cheap -- even for one-on-one instruction.

Guanajuato life centers around the Jardin de la Union, the main town plaza. A salsa band

might be inspiring couples, elderly and young, to dance in public. Later, strolling mariachis could

be performing in the shade of the Jardin’s thick triangular hedge for diners at the sidewalk

restaurants lining one side of the plaza.

A relay of street comedians in mime white face keep audiences in stitches just across the

way, in front of the Teatro Juarez.

From outside the San Diego church next door, strolling minstrel troupes or /{tunas/}in

velvet, 15th century costumes lead tourists through the streets. Those who have paid about $6, get

a ceramic wine carafe as their “ticket” (later filled with a tequila cocktail) and are permitted to

accompany the group during its entire route.

Zack and I met up with the only youth troupe, its members ranging in age from 4 to the

mid-20s. The Tuna Colegiata Real de Guanajuato, which has toured throughout Mexico as well

as Panama and Chile, is composed of polished performers who sing their guts out, five or six

nights a week.

Not knowing the rules, we followed them a few blocks until the singers made a sharp left

up a narrow lane, where paying listeners are separated from the freeloaders. (One guide book

cheekily suggests just tagging along for the free part, but at $6 it was one of the best bargains of

the trip.)

We came back the next night. Since Zack wasn’t an adult, there was no charge, but then

no tequila either. We chatted with one of the performers, a little wise guy named Juan Carlos

Ojedo Castillo, who comically rubbed it in that Zack was technically a “nino.’‘ Another youth

allowed him to try out his guitar. Friendly folks in the crowd translated the lyrics for us.

There are a number of well-trod sites associated with Guanajuato, some not for the faint

hearted.

The most famous is dedicated to mummies, actually bodies preserved naturally by the soil

and climate in the local cemetery and exhumed when upkeep payments stop. There are dead fat

people, dead skinny people and cases filled with partially preserved infants.

La Museo de los Momias, a 25 cent bus ride from the center of town, is one of those stops

you may immediately regret making but really have no choice in the matter. It’s part of the

Guanajuato experience.

The museum says a lot about Mexican culture’s very different relationship with the dead.

And, besides, everybody asks if you’ve seen the mummies. So get it over with.

Mexican tourists packed the museum the morning we arrived. Some react with speechless

unease; others pose their smiling wives and children in front of the displays. An American couple

laughed heartily at the wisecracks their tour guide made about the mummies.

Quite a different site is the Callejon del Beso, or Alley of the Kiss.

There, legend has it, a poor young miner took a room across the very narrow lane from

his beloved. Her father forbade her to meet the lad, but they would lean from their respective

balconies and kiss.

The climax of a Mexican soap opera, Entre El Amor y El Odio/ (Between Love

and Hate) was filmed on the balconies, prompting Mexican and American fans to visit the site,

including Mauricio Martinez, a California policeman and his schoolteacher wife Veronica, who

had their son photograph them while engaged in a public display of affection.

``I always wanted to do that,’‘ Mauricio laughed afterward.

Nearby on the Plaza de los Angeles is a shop that amazes even Mexicans by selling 250

different traditional candies. ``And it’s cheaper than supermarkets -- no middleman,’‘ said the

owner, who with her husband also manufactures many of the items. The most popular are jellied

mummies laid out in rows. They are hard to pass up for sheer shock value but the candied

almonds and crystalized fruits make outstanding gifts for friends back home.

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s likeness is found all over town, but it was her wayward,

genius husband, the muralist Diego Rivera, not Kahlo, who had connections with Guanajuato --

and not exactly congenial ones.

Rivera was born in this conservative, very Catholic community, which wasn’t exactly

enamored of the outspoken leftwing painter. But it turned his childhood home into a quaint little

museum after his death, naming it Museo Diego Rivera. And there’s usually exhibitions by other

artists on the upper floors.

One of my favorite finds was a hole-in-the-wall coffee shop a few doors away. El Conquestador

Café roasts its own beans, so the coffee couldn’t be fresher. The equivalent of 80 cents will

secure a cortado, an espresso with a splash of steamed milk, not unlike an Italian machiato.

The city’s most historic site is the Alhondiga de Granaditas, a mammoth old granary

turned into a museum. It offers a crash course on Mexican revolutionary history. Unfortunately

there are no English explanations, but the displays and murals are well presented.

The building plays an important role in Father Miguel Hidalgo’s ill-fated 1825 uprising

against Spain when his peasant army overran what had become a well-defended fortress. A

young miner, nicknamed El Pipila (Turkeycock), crawled his way to its portals with a stone slab

fastened to his back to serve as bullet-deflecting armor. He was killed while setting fire to the

thick wooden doors, making possible the subsequent slaughter of despised colonial loyalists. For

10 months, Guanajuato served as the insurgent capital.

A monument to El Pipila is on a hillside above the Jardin, and can be reached by a

funicular. The cliff railway ride is fun and the sweeping vista from the martyred hero’s statue is

the best around. Halfway down the hillside is the town’s best Italian restaurant, El Gallo

Pitogorica.

The highlight of our stay was a side trip to the old silver-mining town of La Valencia, a

short bus ride from a stop below the Alhondiga. The mine tour is a waste of time but the local

church, Templo de San Cayetano de Valeniciana, is a national treasure not to be missed.

A wedding was about to commence at the ornately gilded church when we arrived.

A woman approached and, in rapid-fire Spanish, said something about the newspaper I

was reading in a rear pew.

Assuming she meant that the paper should be stowed away, I quickly folded and

stashed it.

A minute later, she returned with another woman who asked in English if they could have

a page to shield the bride as the groom entered the church. I quickly obliged.

The second woman introduced herself as Irma Jimenez, the maid of honor and the

groom’s cousin. She had traveled from Arlington with her Fort Worth boyfriend, Jose

Martinez. A few years earlier, Martinez operated a tailor shop on Park Place Avenue, the street

where we live, and we had patronized his business. Reacquainted we were urged to stay for the

ceremony and then accompany them to the reception.

It was the first marriage for the groom, a Chihuahua-born, 45-year-old schoolteacher, who

was being united with a slightly younger schoolteacher from Guanajuato. We learned at the

reception that it was match hatched in an Internet chat room, but her conservative family were

under the impression they had met, and fell in love, at a teachers’ conference.

Although photography is normally forbidden in the 300-year-old church, the ban was

lifted for the wedding, its chapel festooned in white flowers. Outside a battery of free-lance

wedding photographers pounced, later turning up with finished prints at the reception, where

more photos were taken and delivered.

So the memory of that sweet, unscripted afternoon will endure.